Across the rolling expanse of eastern Colorado and states beyond are green and gold fields of corn, cotton, wheat, soybeans, and sorghum, producing a fifth of the U.S. agricultural harvest and supporting a third of the nation’s livestock production.

For much of the last century, those amber waves of grain have thrived thanks to a vast underground geologic resource that stretches from South Dakota and Wyoming to Texas: the Ogallala aquifer, the largest freshwater aquifer in the world. Drilling and pumping water from the Ogallala aquifer exploded after World War II, and today, 90% of its pumped water is used for crop irrigation.

The Ogallala aquifer is one of the most famous examples of a groundwater resource under pressure from increasing use demands and climate shifts. Since 1950, natural recharge from precipitation has not kept up with the amount pumped, leading to significant water level declines in many parts. Ogallala region communities that depend on this precious natural resource are faced with a reckoning. To stay in the business of feeding the world, business-as-usual irrigation management by farmers cannot be sustained.

Multistate approach

Previous attempts to manage the Ogallala’s depletion have largely been led by individual states’ policies and through voluntary, localized efforts. Over the last several years, Colorado State University has led an unprecedented, multistate approach to extending the use of the aquifer for generations to come, bringing the best scientists and engineers in alignment with the farmers and ranchers who draw from it.

Called the Ogallala Water Coordinated Agriculture Project, the multi-institutional, CSU-led partnership has integrated research, extension, outreach, and thoughtful evaluation of social policies and economic strategies to make science-based recommendations for managing and conserving the Ogallala aquifer. The project, which involved eight Western universities and the USDA-Agricultural Research Service from 2016- 2021, brought together 100 experts, students, and partners through a $10 million grant awarded by the USDA’s National Institute for Food and Agriculture “Water for Agriculture” Challenge. For most of the grant period, the project was overseen by two CSU faculty members: Meagan Schipanski, associate professor in the Department of Soil and Crop Sciences in the College of Agricultural Sciences, and Reagan Waskom, now emeritus professor in the same department and former director of the Colorado Water Center.

“We have focused not just on the science, but on the impact of that science, and on the network our project has helped foster,” Schipanski said. “We’ve become a trusted actor in this multistate space to lead these conversations.”

The team has developed a large body of research across an array of topics related to rethinking the use, stewardship, and conservation of the Ogallala aquifer. Among them: optimizing water use through advanced cropping and irrigation management in both dryland and irrigated production systems; investigating socioeconomic factors that influence water use and decision-making; assessing potential impacts of policy and farm-level practices on regional outcomes; and developing data-based support tools and technologies that are both effective and user-friendly.

Integrated model to inform policy

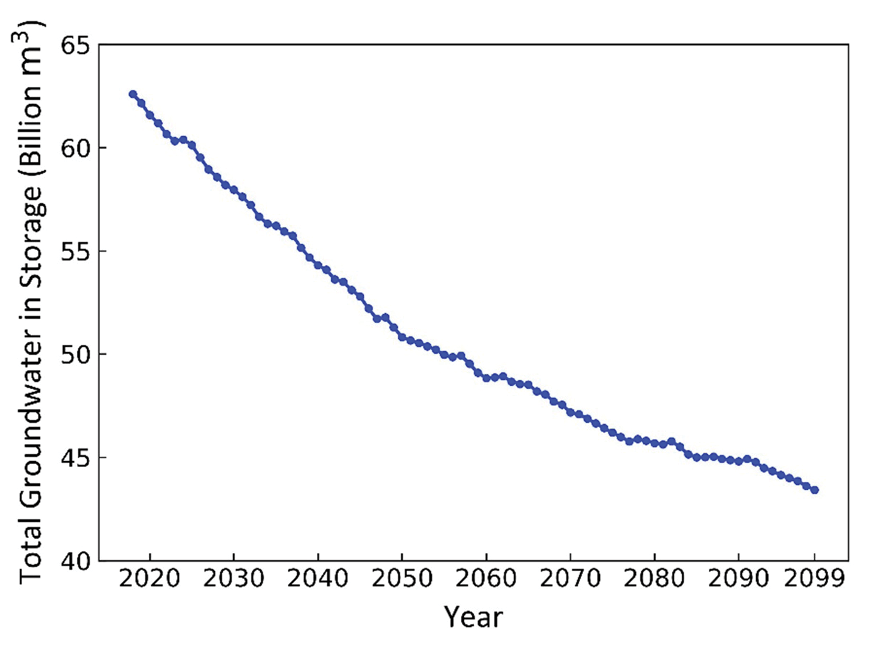

A signature result of this partnership was the development of a complex, comprehensive integrated model that will help inform aquifer management policies for years to come.

A collaboration between researchers in civil and environmental engineering, soil and crop sciences, and agricultural and resource economics, the model encompasses a unique combination of groundwater hydrology, soil type, and producer-focused economic metrics. Its purpose is to support new insights into the delicate tradeoffs, long- and short-term, of water policies in the region.

Prior to the Ogallala agriculture project getting underway, Ryan Bailey, associate professor in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, connected with Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics faculty members, who were studying water policies for the Ogallala region: Jordan Suter, Dale Manning, and Chris Goemans. The economists needed someone to help them link their economic analysis with the physical hydrology of the aquifer system.

“They needed a groundwater hydrologist who could do modeling,” Bailey said. “So I said, ‘Sure, I’d love to collaborate.’” That collaboration continued through the Ogallala project.

Bailey brought in the expertise of then-Ph.D. student and current postdoctoral researcher Soheil Nozari, who spent the next several years constructing and linking a groundwater-flow model to the agro-economic components of the overall integrated model. The tool simulates farm-level planting decisions, water use, and profitability across time.

“By developing and running the models for different water policies, we can let decisionmakers know what the consequences of their decisions are on the aquifer and the profits of farmers,” Nozari said. The modeling framework also accounts for different future climate scenarios and irrigation technologies.

Components work together

The model, which is still being refined, can simulate things such as irrigated land retirement and well retirements, as well as incentives and caps on pumping offered by state and local governments. For example, the researchers used the model to study the efficacy of subsidies paid to producers who reduce groundwater use in Finney County, Kansas, which relies on water from the Ogallala aquifer. The researchers showed that while such a subsidy results in increased well capacities and profitability on average, some producers gain more than others. The model uses well- and field- level information and can provide an educated view of where, why, and how some farms might stand to benefit or not.

Suter, who worked with Bailey, Nozari, and then-postdoctoral researcher Mani Rouhi Rad on the integrated modeling, said the hydrologic, agronomic, and economic models all inform each other; in fact, a complete picture of how water policies affect the region is not possible without all three components.

“As decisions are made to use water in a given year, that affects the hydrology into the next year,” Suter said. “So, you have this kind of dynamic model that allows you to simulate changes in the physical water availability conditions, as well as the behavioral responses to that.”

Bailey said that combining hydrology, soil science, and economics is enormously complex, because those disciplines already have their own languages, technologies, and ways of attacking problems.

“It took a good couple of years to really know how all the pieces were going to fit together,” Bailey added, “and then implementing it was also very challenging.”

Vetting new technologies

The Ogallala Water project has brought together engineering and modeling solutions like Bailey’s team has delivered, along with other tools, insights, and data that correspond to addressing the needs of producers who require guidance and solutions now. That means helping water users change how they approach irrigation or helping them vet technologies that allow them to manage water more sustainably.

One example has been the growth and success of the Master Irrigator Program, first led by the North Plains Groundwater Conservation District in Texas in 2016. The intensive course trains farmers and producers in advanced conservation and efficiency-oriented irrigation practices. Following an eight-state, CSU-led Ogallala Summit in 2018 that featured this program, the Ogallala Water network was able to support adapting Master Irrigator programs for Colorado and Oklahoma.

In Colorado, the Master Irrigator Program launched in early 2020 and was offered again in 2022 in the Republican River Basin, with a second program in the San Luis Valley, according to Amy Kremen, project manager of the Ogallala Water Coordinated Agriculture Project and now associate director of the CSU-led Irrigation Innovation Consortium.

“All in all, we estimate that about 100,000 irrigated acres in Colorado are under management by people who have taken the course,” Kremen said.

Irrigation improvements

Brian Lengel is a producer north of Burlington, Colorado, who irrigates land to support his beef cattle operation. He attended the inaugural Colorado Master Irrigator Program and felt that the reception overall was positive.

“It could be surprising how many irrigated acres get influenced by Colorado Master Irrigator, especially as it moves forward,” Lengel said. “I think water usage could be improved on each farm, and maybe in the 10%-30% savings range.”

Also under the leadership of the Ogallala Water project team, a Nebraska-based program called Testing Ag Performance Solutions, or TAPS, was founded in 2017. Collaborators at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln launched a series of farm-management competitions that provide a no-risk, “try-before-you-buy” environment that introduces farmers to new irrigation technologies as they compete to be the most profitable and efficient at managing a crop. A follow-on TAPS program was launched in 2019 in the Oklahoma Panhandle in cooperation with Ogallala Water collaborators from Oklahoma State University.

Now, with support from a Colorado Water Conservation Board grant, the CSU-based Irrigation Innovation Consortium will spearhead a TAPS program at the Agricultural Research, Development and Education Center in Spring 2023, Kremen said.

Kremen said the work of the Ogallala Water team will be felt for generations to come, and that, above all, getting producers, scientists, and engineers on the same page has been its most valuable outcome.

“Given the nature of the region’s water-related challenges, an all-in effort by everyone is needed,” Kremen said. “The way our team went about research and engagement, respecting and drawing on the expertise of producers, water districts, departments of agriculture, water resources boards, and so many other individuals and groups, it has been incredible to get to be part of this ongoing conversation. This project boosted networking and trust within and across state lines much faster and extensively than might have happened without our team’s work. I’m really proud of how the team has helped people come together.”