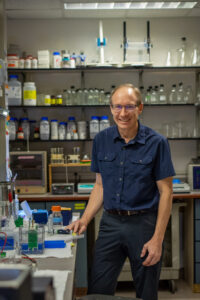

Olve Peersen works in his lab at Colorado State University (Nikky Sims, CSU College of Natural Sciences)

The emergence of SARS-CoV-2 – the virus that causes COVID-19 – changed the world, and its perpetual evolution has continued to keep it in the headlines, with different variants creating new puzzles for vaccine manufacturers and public health officials working to navigate how to respond to an ever-changing threat.

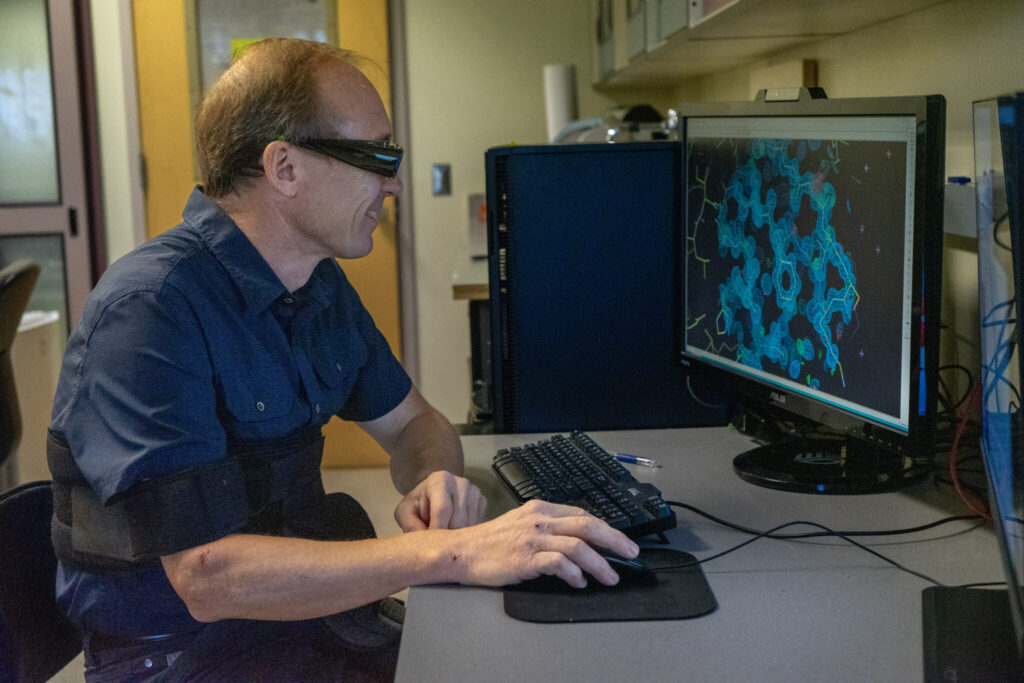

It’s a real-world example of the importance of the work that happens in Colorado State University Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Professor Olve Peersen’s lab. For years, his team has worked to better understand the mechanisms behind how RNA viruses replicate and mutate, information that could lead to better treatments and vaccines for both new and emerging pathogens.

“My work has been about understanding the fundamentals of how these different virus genomes are replicated and how certain enzymes work and make mutations,” Peersen said.

The National Institutes of Health has supported Peersen’s research since 2004, and he recently received a $3.8 million MERIT Award to continue this work for the next 10 years. These awards provide long-term, stable support to impactful research, and are only given to 5% of investigators who receive NIH funding.

How do viruses mutate?

The evolution of a virus starts with enzymes called polymerases that are responsible for replicating the viral genetic code. Sometimes these enzymes make mistakes, which can lead to mutations that could either stop a virus in its tracks or lead to new variants that later replace previous incantations of a virus.

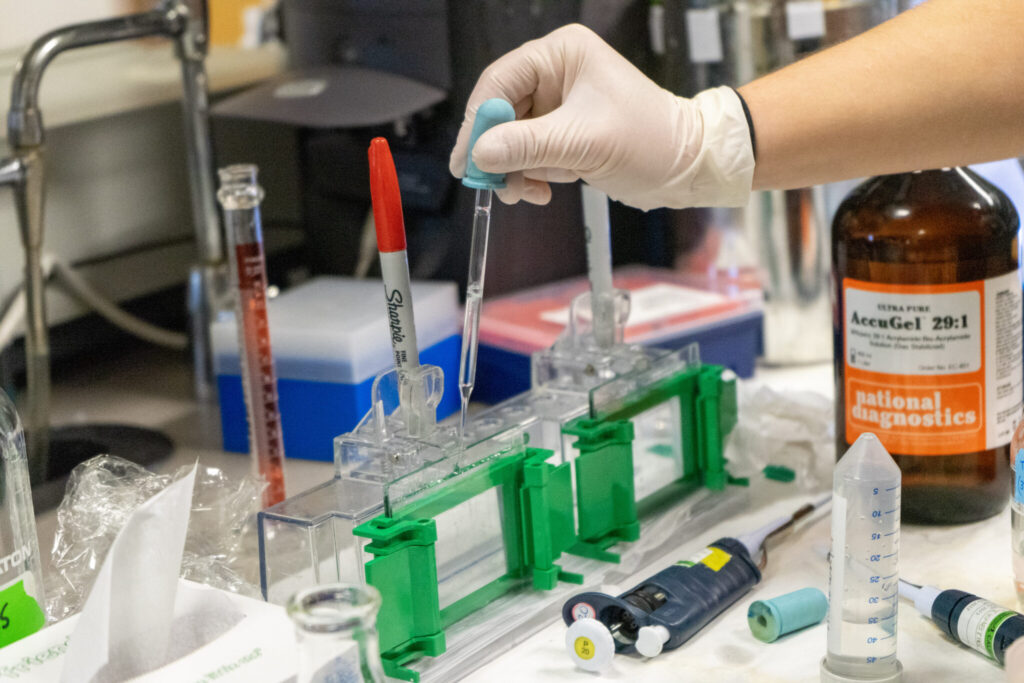

Peersen’s research focuses on forcing polymerases to make mistakes in a lab setting. Doing so allows him to compare how different mutations can impact a virus’ ability to continue to replicate, as well as the speed with which different pathogens evolve over time.

“Somewhere between 20-50% of mutations are lethal in some way, but the rest are viable enough for a virus to replicate and continue to evolve,” he said. “RNA viruses can easily generate mutations and rapidly select for those mutations that are better than the starting virus.”

Peersen’s earlier work has focused on poliovirus and coxsackievirus – the viral infection that causes paralysis and hand, foot and mouth diseases. These are some of the smallest viruses that affect humans, but nevertheless they still evolve just as quickly as larger pathogens. They also have small polymerases, and that allowed him to determine the atomic level three-dimensional structures of their polymerases and figure out how these molecular machines work to replicate the viral genome.

“The principles that we learn from these smaller virus polymerases can be applied to more potent and dangerous viruses,” he said.

Those larger viruses include everything from Dengue fever and West Nile to coronaviruses like SARS-CoV, whose evolution is the focus of Peersen’s more recent research.

“What we’ve discovered with the SARS polymerase is interesting in that its core structure is just like polio polymerase and it basically works the same way as the polio enzyme does, however it’s four to five times faster,” he said. “With that being said, it does not make four to five times as many mistakes.

“What we’re trying to learn is how the SARS polymerase can reign in those mistakes better than other viruses.”

Providing important knowledge for future pandemics

(Photo by Nikky Sims, CSU College of Natural Sciences)

The emergence of new variants like omicron have necessitated updates to the existing vaccines meant to protect against COVID-19 – and this same principle applies to other viruses as well.

Peersen’s research could give drug makers tools to create vaccines that use weakened versions of viruses that provide a low-level infection but mutate less than the version circulating in the population, giving the immune system the opportunity to adapt and offer more protection against potential variants.

Studying how viruses mutate can also help drug manufacturers potentially create treatments that can disrupt the replication of a virus.

“If we understand how these mechanisms work, then we can find a way to manipulate how they function,” Peersen said.